The name ‘Christian’ (Χριστιανός) gets a mere 3 mentions in the entire New Testament. When referring to Jesus’s followers and members of the early church, the biblical writers much prefer the word ‘disciple’ (μαθητής), using it over 250 times.

Maybe that’s a good thing. You’ve probably noticed that many in today’s world don’t particularly like Christians. I can’t really blame them; some days, I don’t even like us. Most people wouldn’t have a problem associating with Jesus, but they would have a problem associating with many of Jesus’s associates, especially when those associates are associated with:

- blind allegiance to a secular political philosophy.

- angry fire-and-brimstone rhetoric against perceived ‘enemies’ (Muslims, liberals, feminists and gays, to name a few).

- ‘holier-than-thou’ elitism.

- the Puritanical policing of public morality.

- blatant hypocrisy, vis-a-vis (as a most recent example) enthusiastically supporting a man who ritually contravenes the very morality they insist upon.

Yeah, this stuff just kills us.¹ And let’s be honest, over time, we’ve earned this reputation. I know I have, thanks to proudly wielding many of these traits in years gone by.

Becoming Disciples

Behind all this lies our perception of what makes a ‘Christian’. Very often, for us in the Western church, being a ‘Christian’ means assenting to an accepted set of theological and Christological propositions and doctrines. A ‘good Christian’ also follows a fixed scheme of religious behaviours, even established modes of patriotic and political expression. In short, being a ‘Christian’ means believing, doing and saying the ‘right’ things.

Yet our holy Christian quest for doctrinal, religious and civic purity is a far cry from the life of discipleship championed by Jesus and the apostolic church.

Now, ‘discipleship’ – that’s a loaded word in many churches, which might mean:

- the six- to eight-week course for ‘new believers’, meant to straighten them out with a solid theological grounding.

- a menu of optional extras you can add on, once your vehicle to heaven has been purchased – like a Christian sat nav or rear camera assist.

- a higher calling, meant only for the truly spiritually evolved, but not necessarily undertaken by the rank and file, who are just happy to be ‘saved’.

However, the contemporary and 1st-century notions of discipleship don’t match. What did discipleship mean for Jesus and his earliest followers?

A Life of Commitment and Self-Denial

Becoming Jesus’s disciple in the 1st century required absolute commitment. The gospels stress the point that Jesus’s disciples left everything they had to follow him wherever he went (e.g. Mark 4:18-22, Luke 5:27-28, Matthew 19:27). The expectations he had for disciples sound harsh to our ears:

Another of his disciples said to him, ‘Lord, first let me go and bury my father.’ But Jesus said to him, ‘Follow me, and let the dead bury their own dead.’

Matthew 8:21-22, NRSV

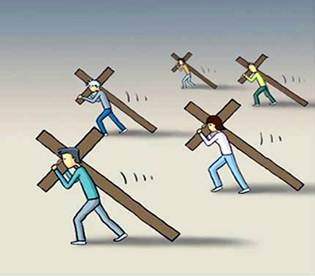

Whoever loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me; and whoever loves son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me; and whoever does not take up the cross and follow me is not worthy of me.

Matthew 10:37-38, NRSV

Ouch. Sure, he used some classic Near-Eastern hyperbole here, but clearly left no room for half measures and divided loyalties. And through the very ugly image of ‘taking up the cross’ (crucifixion was such a brutal and hideous thing, it wasn’t mentioned in polite conversation in the Roman era), Jesus showed he wasn’t offering an easy, complacent life of privilege, but one of sacrifice and self-denial.

A Life of Imitation and Transformation

Jesus didn’t recruit disciples to instruct them in systematic Reformed theology, teach them the doctrines of propitiation and substitutionary atonement, regulate their moral behaviour, or even – wait for it – to tell them how to get to heaven. No, Jesus recruited for relationships, built on obedience and imitation. He called his true disciples to remain relationally connected to him (John 15:1-11), following his way of life and obeying his teachings and commands.

Jesus didn’t recruit disciples to instruct them in systematic Reformed theology, teach them the doctrines of propitiation and substitutionary atonement, regulate their moral behaviour, or even – wait for it – to tell them how to get to heaven. No, Jesus recruited for relationships, built on obedience and imitation. He called his true disciples to remain relationally connected to him (John 15:1-11), following his way of life and obeying his teachings and commands.

The writer of I John says it best:

Now by this we may be sure that we know him, if we obey his commandments. Whoever says, ‘I have come to know him’, but does not obey his commandments, is a liar, and in such a person the truth does not exist; but whoever obeys his word, truly in this person the love of God has reached perfection. By this we may be sure that we are in him: whoever says, ‘I abide in him’, ought to walk just as he walked.

I John 2:3-6, NRSV

This deliberate imitation of Jesus, journeying with him in relational obedience, naturally brings about both inward and outward transformation – an organic transformation, which propositional assent or subservience to rules and codes could never achieve.

A Life of Disciple Making

In one of his most well-known commands to his disciples, affectionately and sometimes solemnly called ‘The Great Commission’, Jesus told them to ‘disciple the nations’ as they went about in the world, teaching those disciples to obey his commands (Matthew 28:19-20).

Just how did he want them (and us) to do that? I may be guessing here, but I don’t think he intended his followers to mock people, yell at them that they’re hell-bound, vilify them for their immorality or legislate codes of conduct and force others to adhere to them. Rather, I think that he expected them (and us) to invite others into the same course of discipleship they were undertaking: imitating Jesus and learning to obey him, undergoing fundamental change in the process.

A Journey of Relationship

For us, choosing to emulate Jesus should go far beyond ticking theological and behavioural boxes. That’s excellent news, because hell, I can barely get out of bed with a smile, much less make it through the day acting like a ‘good Christian’. I’m a flawed, broken and sometimes anxious mess. None of us have power, in and of ourselves, to affect such a transformation.

What we bring is intention, a desire and commitment to submit to Jesus and to learn from him. It’s a lifelong journey, a developing relationship, with all the twists and turns, ups and downs you’d expect. Make no mistake – it’s him that does the hard yards. He teaches us to surrender control of more and more of our lives and, in the process, changes us into more and more of his likeness.

And we shouldn’t be surprised if ‘walking as Jesus walked’ turns out not to involve much of what we currently equate with being ‘Christian’. In fact, a major step for us, I believe, will be to humbly lay down our existing attitudes and preconceptions about ‘Christian living’, to yield them to Jesus and accept that he’ll likely alter them.

Proud to Bear the Name

Peter wrote to his own disciples, who were suffering persecution as ‘Christians’. It wasn’t a name they had chosen for themselves, but one others had given to them. Nonetheless, Peter encouraged them to be proud that they bore that name (I Peter 4:16).

We can also be proud to bear that name, if ‘Christian’ once again refers to people who walk as Jesus walked. We can be proud when the name ‘Christian’ once again refers to disciples of Jesus.

¹ A word of caution here. If we’re not careful, we can easily insert a brand new set of ‘Christian’ standards here, such as caring for the environment or feeding the poor, making them the new litmus test by which we rate our ‘Christianity’ against others’. Don’t misunderstand me, I believe these are noble pursuits, perfectly in keeping with a biblical understanding of the world. But they ought to result from a humble response to Jesus and his gospel, not be imposed as the new boxes for ‘true Christians’ to tick.

Image Credits:

- Feature Image: Carrying Crosses (from the creatively titled ‘Joe’s Blog’, http://manualoflife.com/joeen/?p=2528)

- The resurrected Jesus and his disciples (from the Scottish Catholic Observer, http://www.sconews.co.uk/opinion/22041/the-three-levels-of-christian-discipleship/)

Leave a Reply