William Shatner is an icon of our times. Who could forget that episode of the Twilight Zone where he opens the airplane’s emergency door at 20,000 feet to put six slugs into the fuzzy gremlin tearing apart the wing? And if you’ve never heard Shatner’s version of ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’ (from his album of spoken word, The Transformed Man), you’ve missed a life-altering experience. Until now:

Of course, we’ll always remember William Shatner as the redoubtable James T. Kirk. In his almost-final outing as captain of the U.S.S. Enterprise, Starfleet sends Kirk to initiate peace talks with the Klingon Empire. The potential end of the protracted conflict between the Klingons and the United Federation of Planets is good news for the galaxy.

But it’s not good news for everybody. A shadowy cabal of high-ranking figures, from both the Federation and the Empire, conspire to sow discord, to murder, even to frame Captain Kirk himself, in order to scuttle the peace process. These individuals have built their careers, their power and their influence through the longstanding hostilities and have no interest in any change to the status quo.

Whose Good News?

The gospels tell a similar story. Along comes Yeshua ben Yosef bringing good news: the Kingdom of God has come near! The time is at hand to set things right, to replace broken systems with heaven’s order, to end oppression and injustice, to lift up those who have been trampled upon, to heal and restore the world. And you’re welcome to change direction and enter this kingdom!

Yet this wasn’t good news for everybody.

This wasn’t good news for the Romans. They intended to squash any kingdom that even remotely threatened their iron grip on power. Let’s not imagine that Pilate lost too much sleep over crucifying another Jewish rabbi. His intended satire of the sign on the cross was clear: this is what happens to would-be ‘kings’. Here’s what we think of your ‘good news’.

The chief priests in Jerusalem didn’t see Jesus’ proclamation as good news either. Their authority resulted from an (albeit uneasy) alliance with the Roman overlords, who had appointed them to their positions. They didn’t approve of anything or anyone that would upset this tenuous balance.¹ They also knew full well that the kind of kingdom Jesus was talking about would spell the end of their grip on power.

Nor was it good news for Herod Antipas. The Romans had already broken apart the client kingdom of his father, Herod the Great. They allowed Antipas to pretend to be a real king, clinging to his small enclave of Galilee and the Trans-Jordan. Any mention of a new and coming kingdom was obviously a threat to what remained of his own.

Not even the Pharisees would get on board. Funny, because they seemed to share some common ground with Jesus. They too aimed to prepare people for the arrival of the Kingdom of God. They too spoke of the eventual resurrection of the dead for the faithful.

However, the Pharisees, as a rule, tended toward a rugged nationalism. Though wielding no political authority under the Romans, they were an influential and vocal pressure group (comparable to today’s Christian Right, or the ACLU, or the NRA). The Pharisees insisted on maintaining the Jewish national and ethnic identity. Enter Jesus, who seemed to them to tread nonchalantly over the markers of that identity, with his apparently relaxed attitude about the Sabbath and the dietary regulations and the stipulations of the Torah. What was more, he invited people into the Kingdom (prostitutes, and tax collectors – who were essentially Roman collaborators – and other low-rent types, ignorant of God and the Law) that the Pharisees thought were best left out. Add to this that Jesus undermined the Pharisees public image and we can see why they served as his regular sparring partners in the gospels.

However, the Pharisees, as a rule, tended toward a rugged nationalism. Though wielding no political authority under the Romans, they were an influential and vocal pressure group (comparable to today’s Christian Right, or the ACLU, or the NRA). The Pharisees insisted on maintaining the Jewish national and ethnic identity. Enter Jesus, who seemed to them to tread nonchalantly over the markers of that identity, with his apparently relaxed attitude about the Sabbath and the dietary regulations and the stipulations of the Torah. What was more, he invited people into the Kingdom (prostitutes, and tax collectors – who were essentially Roman collaborators – and other low-rent types, ignorant of God and the Law) that the Pharisees thought were best left out. Add to this that Jesus undermined the Pharisees public image and we can see why they served as his regular sparring partners in the gospels.

And these influential groups and individuals, who despised each other at the best of times, colluded to eliminate Jesus, and his good news along with him.

Rulers and Authorities, Beware!

That’s the kind of reaction we should expect to the Kingdom of God. We shouldn’t be surprised when leaders and luminaries, whose power springs from and rests upon the corrupt systems of the world, seem less than enthused about the kind of kingdom Jesus announced. Here’s a kingdom that stands power as we know it on its head. Here’s a kingdom, not for the wealthy, or the proud, or the strong, or the violent, but for the meek, the poor, the merciful and the peacemakers. Here’s a kingdom that elevates the slave to the highest position and knocks the elites off their pedestals.²

In fact, this kingdom is a danger to the rulers of the world! God has no intention of negotiating a power-sharing agreement with any of them. The Kingdom of God will do away with our politics, our economics and our social order. And heaven help those who hang on by their fingernails to the sinking ship.

In light of this reality, we ought to examine not just our leaders, but ourselves. Have we become so enamoured with our own politics (or our own side of a politics), with our free market, with our religious structures, or our own positions in the social hierarchy, that we’d actually lament seeing those systems vanish? Would we find ourselves in the gospel story, not as disciples, but as the chief priests or as the Pharisees – afraid of the good news of the Kingdom that Jesus described and lived?

Because despite every effort of the political and religious forces that conspired to crucify Jesus, his good news couldn’t be stopped. Three days later, it was back, bigger than ever. And therein lies the message to us and to the present powers-that-be: like it or not, the Kingdom of God is coming!

The Kingdom of God is the key focus of scripture and the message of Jesus. That’s why I’ll be writing exclusively about the Kingdom for the next year. You can view all of the the pieces in the series on this page.

¹ The chief priests, Josephus suggests, would have been members of the Sadducees party (who may have taken their name from Zadok, the biblical high priest from Israel’s golden age). The Sadducees comprised the upper crust of Jewish society. Unlike the Pharisees and the general population, they didn’t subscribe to any belief in a resurrection, or even an afterlife. As N.T. Wright explains, Sadducees would want to tamp down the idea of a resurrection, as it would encourage hot-headed revolutionary types, with no fear of death, to endanger the fragile positions they had carved out for themselves.

² Ever notice how little Jesus’ teachings from the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew, or its parallel, the Sermon on the Plain in Luke, are cited or even mentioned by politicians – or, sadly, by the Christian leading lights who support them?

Image Credits:

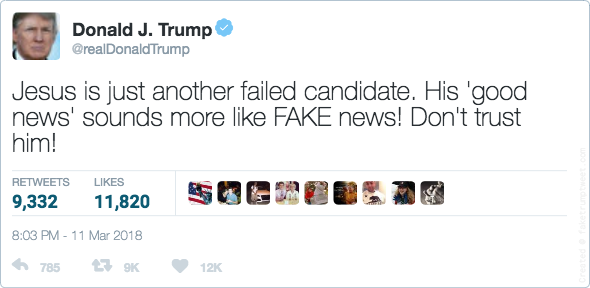

- Feature Image: A FAKE Trump tweet, which I was able to make with the help of the good people at FakeTrumpTweet.com

- The coin of Herod Antipas. He used the image of a Galilean reed rather than one of his face so as not to offend his Jewish subjects. When Jesus talked about ‘a reed shaken by the wind’, everyone would have known he was talking about Herod. (By Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2417312)

- ‘Jesus Denounces the Scribes and Pharisees’ etching by Friedrich August Ludy

Leave a Reply