Patty vs. The Minions of the Antichrist

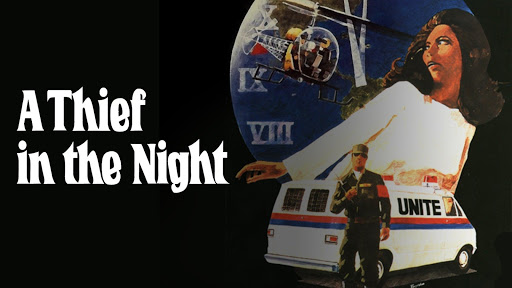

t’s a Wednesday evening, around the time of the Gulf War. I’m in a narrow rectangular room with around fifteen other boys, members of our church’s Boy’s Brigade group (a Christian version of the Boy Scouts). A television and VCR are positioned at one end of the room and the lights are off. Tonight, for our edification and viewing pleasure, our leaders are showing the 1972 low-budget Christian classic, A Thief in the Night.

Riveted to the screen, I watch the travails of the hapless Patty. Her bright yellow alarm clock awakens her one morning to find her husband’s buzzing electric razor in the bathroom sink, but with no husband attached to it. News reports begin to come in that all of the world’s (true) Christians have mysteriously vanished.

From there, things quickly go pear-shaped. A silver-tongued government official, now calling himself ‘Brother Christopher,’ seizes the moment and forms a one-world government organisation called UNITE to maintain order and stability. All citizens are expected to take the new government’s ‘mark’ on their right hand or their forehead. Without it, they won’t be able to purchase goods or receive medical care. Men, women, young and old line up dutifully to be stamped.

Patty, though, remembers the warnings of now-departed Christian friends about a ‘Mark of the Beast’ and she goes on the lam. Soon she is pursued through the streets by the full might of UNITE – two guys in a white Chevy van – and eventually captured. Patty languishes in prison for the duration of the next film in the series, before facing execution. Strapped to a guillotine (because apparently, the Antichrist and his minions think the instigators of the French Revolution were onto something), she cries out to be given the Mark of the Beast. Oh Patty, what doth it profit you to take the Mark, but lose your soul?

The whole interpretive system of dispensationalism (let’s call it ‘Left Behind theology’), from which ideas like the Rapture, the Antichrist and his one-world government emerge, is rife with so much bad teaching, it’s hard to know where to begin.

Yet the so-called Mark of the Beast has generated much renewed fear in recent years, associated by some Christians with the COVID vaccines – just the latest in a litany of Mark-of-the-Beast potentials that includes credit cards, microchips and UPC codes. Because such fear is unhelpful, unnecessary and unsupported by the biblical text, the Mark of the Beast seems like a great place to start.

Everyone is Marked

The idea of the Mark of the Beast comes from Revelation, a stunning work of Christian art composed by John of Patmos. On the whole, it’s an apocalypse, a popular genre in the centuries before and after Christ. The purpose of an apocalypse isn’t to predict some future calamity, but to reveal the spiritual realities behind events in the present – the audience’s present. And the present for John’s Christian audience was consumed by the Roman Empire, with its wealth, power and religious practices, both alluring and insidious. John writes to that audience with a stark choice: compromise with Rome, its idolatry and its way of life, or remain fiercely loyal to Jesus and his kingdom, facing whatever consequences might result. There is no middle ground.

Apocalyptic literary works communicate in symbol and Revelation is no exception. Chapters 12-14 present an epic tale of the Dragon (the satan), who makes war upon God and upon God’s people. As part of that agenda, the Dragon calls up a beast from the sea, John’s symbol for the Roman Empire 1. Another beast, this one from the land, rises next and directs the world to worship the beast from the sea:

It forces everyone—the small and great, the rich and poor, the free and slaves—to have a mark put on their right hand or on their forehead. It will not allow anyone to make a purchase or sell anything unless the person has the mark with the beast’s name or the number of its name. Revelation 13:16-17, Common English Bible

There it is, the Mark of the Beast, his name or the number of his name 2, stamped upon the worshippers of the beast. But they’re not the only ones who are marked. In the next passage, we see the people of God, John’s audience, symbolised as 144,000 people 3 (drawn from the 12 tribes of Israel). They, too, bear a name on their foreheads:

Then I looked, and there was the Lamb, standing on Mount Zion. With him were one hundred forty-four thousand who had his name and his Father’s name written on their foreheads. Revelation 14:1, Common English Bible

What we see in these passages is that everyone is marked. You either bear the beast’s name or the Lamb’s and His father’s names upon you. Again, there is no middle ground.

The Mark is Symbolic

Of course, no one in John’s audience was running about with a physical brand on their foreheads. They would recognise John is referring to a symbolic mark, signifying their allegiance to God and to the Lamb.

John (who loves to allude to the Hebrew Scriptures) probably has passages like these in mind:

Only unleavened bread should be eaten for seven days. No leavened bread and no yeast should be seen among you in your whole country. You should explain to your child on that day, ‘It’s because of what the Lord did for me when I came out of Egypt.’ “It will be a sign on your hand and a reminder on your forehead so that you will often discuss the Lord’s Instruction, for the Lord brought you out of Egypt with great power." Exodus 13:7-9, Common English Bible

"Place these words I’m speaking on your heart and in your very being. Tie them on your hand as a sign. They should be on your forehead as a symbol." Deuteronomy 11:18, Common English Bible

If the mark upon the people of God in Revelation 13 is symbolic, then we should expect (for sheer literary balance, if nothing else) that the mark upon the worshippers of the beast a few verses before is also symbolic.

You Don’t ‘Take the Mark’ Accidentally

These two symbolic marks simply denote who’s who. Those who follow the beast – those who indulge in or flirt with Roman power, greed and religion – are marked accordingly. Those who remain loyal to Jesus are likewise marked. The choice is the mark. And theoretically, one could switch their allegiance and take on the opposing mark.

So relax. That vaccine you received for the sake of your health wasn’t the Mark. That QR code you scanned at the sushi restaurant you visited last Wednesday wasn’t the Mark. The microchip in your credit card isn’t the Mark, and God isn’t putting ‘Xs’ against your name each time you tap to pay.

John’s concern was the power of human empire, power that set itself against the Kingdom of God. We should cease the constant hand-wringing over what the Mark of the Beast might be and instead ask ourselves, what power do we need to resist? What are the empires whose ways and practices and very existences oppose Jesus’ kingdom? 4

In the end, the real question is, whose mark are we now choosing to bear?

Notes:

- Here, readers steeped in ‘Left Behind theology’ may cry foul. It’s a common teaching that the beast from the sea represents a coming Antichrist figure. However, the scriptural allusion John is drawing upon here is from Daniel 7, where four beasts are pictured, which clearly symbolise four empires – an angel basically tells Daniel that. It makes sense, then, to interpret Revelation’s ‘beasts’ along the same lines. This is how sound biblical scholars like N.T. Wright, G.B. Caird, Richard Bauckham, Ben Witherington III, Craig Keener and Craig Koester all interpret this passage.

- The ‘number of his name’ refers to the ancient practice of gematria. Hebrew, Greek and Latin had no numerals as English does. Instead, letters were used to represent numbers (think ‘Roman numerals’). Because of that, people played a game by adding up the numbers spelled out by the letters of people’s names. We even have this coy bit of graffiti from Pompeii: ‘I love her whose number is 545’ – the Roman equivalent of the love notes you used to pass around at study hall. In Revelation 13:18, John invites the reader to do the maths and figure out who he’s referring to: ‘This calls for wisdom. Let the person who has insight calculate the number of the beast… That number is 666.’ The number ‘666’ is one way to render Nero’s name, suggesting that John has in mind either Nero, or a ‘new Nero’ leading the Empire in persecution of the church. Can we confirm something like this is the safest reading? Yes! Another way to render Nero’s name (from Latin instead of Hebrew) is ‘616’ – and indeed, we have early manuscripts of Revelation where ‘616’ is given as the beast’s number… as though a later scribe understood the reference to Nero and adjusted the number for Latin thinkers.

- Again, in ‘Left Behind teaching’, you may have heard the 144,000 interpreted as a literal group of set apart and ‘sealed’ Jews who serve as witnesses for Jesus during a 7-year ‘Tribulation’ period. There are a few reasons why this isn’t the best reading: 1.) While theologians of different stripes disagree on what the images of Revelation symbolise, they all agree images like the those of the beasts, or the Lamb, or the four horsemen are symbols. It make little sense to read image after image as symbol, then suddenly to switch to a literal reading for the image of the 144,000; 2.) There is always a contrast in Revelation between what John hears and what he sees. For example, in Revelation 5, John hears of the ‘Lion of the Tribe of Judah’. When he turns to look, he sees a slaughtered lamb. So in Revelation 7, when John hears 144,000 servants of God from the 12 Tribes are to be sealed, we shouldn’t be surprised what John sees is a great multitude of God’s people from every tongue, tribe and nation.

- It’s ironic, I suppose, that the heartland of dispensational theology is found among the Evangelical and Pentecostal churches of America (it enjoys nowhere near the same level of buy-in among Christians elsewhere). They are most concerned about a coming Mark of the Beast – yet so many happily cooperate with American empire and civic religion.

image sources

- WMT-UPC-articleLarge: New York Times Magazine

- Thief in the Night: Rotten Tomatoes

Leave a Reply