Renee and I were once in the soul-saving business. Not in a comfortable metropolis like Tokyo, or Singapore, or some European capital, either. We fancied ourselves the kind of hot-shit missionaries you read about in books and magazines: trekking through remote parts of East Asia where the average Westerner fears to tread, carrying modest-sized backpacks stuffed with only the essentials, eating whatever obscure and unholy parts of animals were put before us, sleeping on rice sacks and hard floors – all with the dream of evangelising the population, person by person and village by village.

I suppose the soul-saving business really was a business, too, since an assortment of supporting churches and private well-wishers paid us to do it. As professional soul-savers go, though, we weren’t model employees. Our missionary prayer cards may still be hanging on our former supporting churches’ ‘Walls of Shame’. And the wet weather we would often encounter on our trips to the villages? Maybe those were God’s tears. I don’t know. The point is at the conclusion of our years of toil, our confirmed soul count stood at zero. I wouldn’t even be surprised if the number was negative and we had driven a few souls away.

Now, to be fair to ourselves and the many committed and honourable people serving with us, few of us would have framed our work in that way. We wanted something more than just a litany of half-hearted responses to a ‘gospel presentation’. Most of us, too, cared deeply about the wellbeing of local people and their communities in the here and now. Yet it’s hard to dispute that the long-standing focus of popular evangelicalism has been the afterlife. It preaches a message of ‘personal salvation’, collecting human trophies to line the golden streets of heaven, rescuing their souls from the fires of hell.

Our Choice of Words

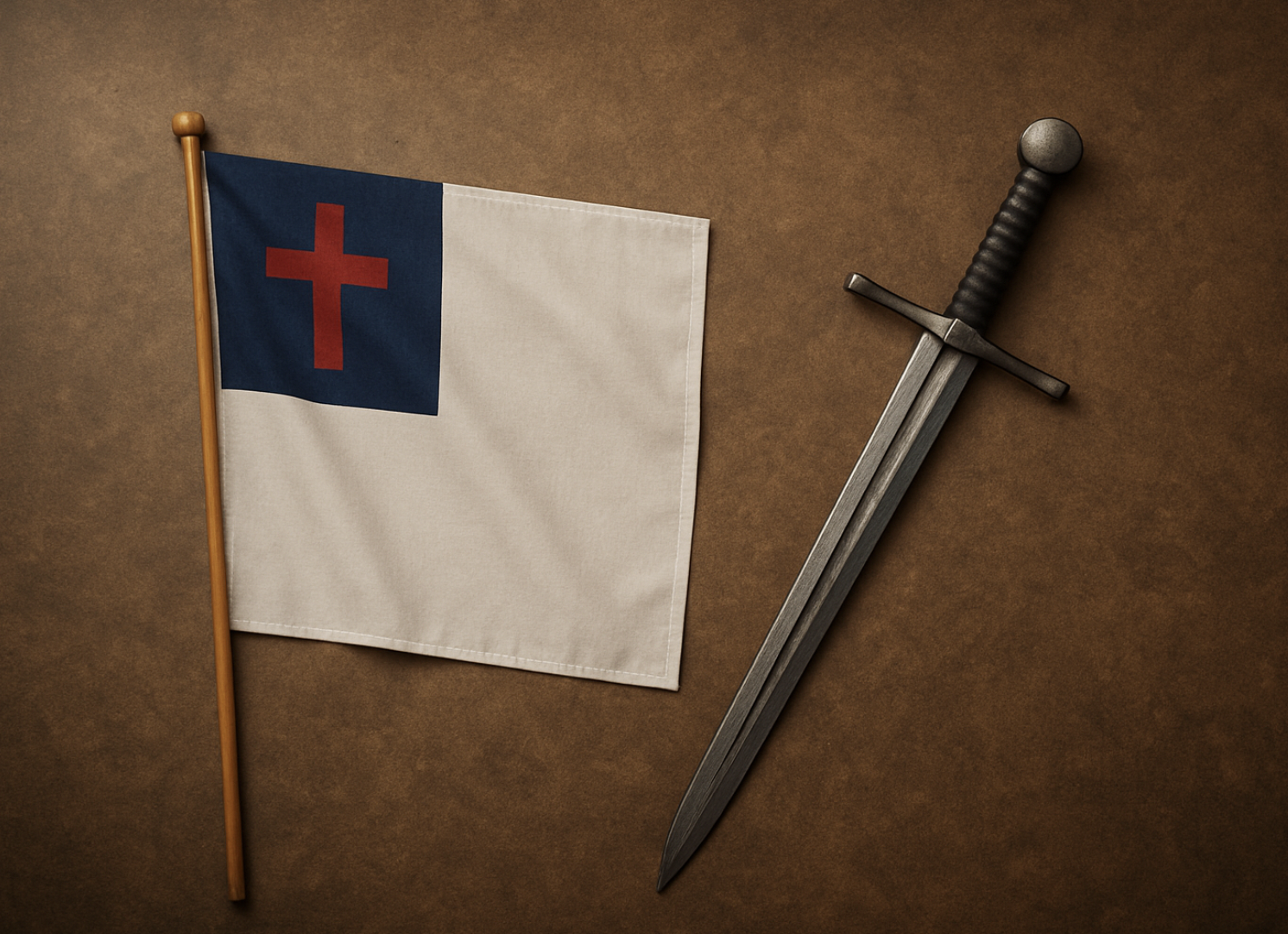

In short, mainstream evangelicalism plays a numbers game. And it often feels like a conquest. Unfortunately, Christianity has many shameful episodes of violent conquest in its history. Has evangelicalism of, say, the last two centuries merely adopted a milder version of it?

We missionaries often used ‘warfare’ language on the field, as though we were playing a colossal round of ‘Risk’ on God’s behalf, facing off against the devil and his minions, rolling the dice to capture the eternal souls of humankind. Every individual was a potential skirmish. Every community was a battlefront. We were ‘taking ground from the enemy’ as we increased the Good Place’s market share of the human population. All for the glory of God.

This type of language hasn’t disappeared in the intervening years. Many American churches and Christian organisations lean in hard to ‘conquest’ ideology. Their pastors and leaders and luminaries speak of worship and prayer (the more expressive, the better) as forms of combat, a kind of spirit-realm krav maga. Beyond the worship service, they sanction an invasion of vital sectors of secular culture – education, entertainment, media, business, etc. – by Christians. The right kind of Christians, anyway. This is by no means the fringe; this is a prominent, maybe even the dominant, sector of American Christianity.1

We missionaries often used ‘warfare’ language on the field, as though we were playing a colossal round of ‘Risk’ on God’s behalf, facing off against the devil and his minions, rolling the dice to capture the eternal souls of humankind.

Do evangelicals and charismatics have a point? Jesus, after all, did teach about “entering the strong man’s house” and “tying him up” to “steal his possessions”. From the context, it’s clear the “strong man” in question is the satan. Yet, also from the context, Jesus is answering the specific charge that he himself is in league with the satan and using the enemy’s power to perform miracles. Does Jesus look at our battle for the afterlife, or our assault on cultural institutions, and think, “Yeah, this is what I was talking about”? I’m not so sure.

Common Cause?

More than that, I wonder if a ‘conquest’ mindset within evangelicalism has made it especially susceptible to the allure of nationalism. The drive to occupy and control territory, the gathering of souls around a flag, the call to work for the glory of the nation, the promise of a future ‘utopia’ for the true believers – these are some of the calling cards of nationalism. So it’s not hard to see how evangelicals might find a kind of common cause with it.

And they do. Few bother to keep it a secret, either. Hordes of today’s evangelical leaders and congregants proudly trumpet their Christian nationalism: their belief that America is and should be a Christian nation, that the levers of government and the judiciary must be pulled to make it so, that only a Christian America can fully prosper and dominate the world, militarily and economically. National glory and conservative political interest have encroached so much on the teachings of Jesus that it’s hard to say what measure of them remains in the average American evangelical. I’m not sure he or she can tell the difference anymore.

I suppose it’s ironic that we who love to quote Paul on “wrestling not against flesh and blood, but against principalities and powers” (Eph. 6:12) would gleefully succumb to nationalism, one of the most brazen and least subtle ‘principalities’ of all.

Learners, Not Conquerers

Has the evangelical thrust toward ‘sinner’s prayers’ and ticking the afterlife box helped to lead us to this point? That’s an open question. What I am sure of is that Jesus never asked us to conquer territory and capture souls; he asked us, instead, to make disciples. Disciples learn. They strive to hear the words of their teacher and to emulate his way of life.

I suggest that if evangelicals’ focus was on making disciples committed to the way of Jesus, rather than just converts, we’d be far more resistant to nationalism. That will mean adopting the mindset of mentors – or better yet, fellow travellers – and abandoning the mindset of conquerers.

- This theology is known as dominionism, and has been popularised by people like Bill Johnson, Lance Walnau and Francis Schaffer. One iteration is known as the ‘Seven Mountain Mandate’, in which each ‘mountain’ symbolises a major sector of culture and society, over which Christians are called to exert as much influence as possible. A particularly strident and overtly political version of dominionism is the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR), with which people like Paula White-Cain, Charlie Kirk and Marjorie Taylor Greene have aligned themselves.

Leave a Reply